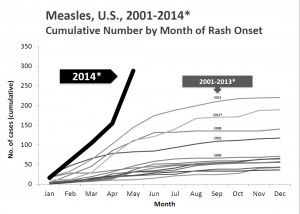

Measles is back in the news this year, and the latest epidemic began with unvaccinated people who traveled overseas to the United States and spread it among a cluster of other unvaccinated people.

There were 288 cases of measles documented in the first five months of this year, according to recently released data from The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The major clusters have been in California, Ohio and New York City. Of those 288 cases, about 1 in 7 people were hospitalized.

About 90 percent of those who contracted measles were unvaccinated, and in virtually all cases, these people chose not to get vaccinated for philosophical or religious reasons, says Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

“They chose to put themselves at risk,” Dr. Offit told Medscape earlier this year.

Fighting Misconceptions

Unfortunately, neither the latest increase nor its cause shocks pediatricians who have plenty of experience trying to convince wary parents their child will be safer for having been vaccinated.

Unfortunately, neither the latest increase nor its cause shocks pediatricians who have plenty of experience trying to convince wary parents their child will be safer for having been vaccinated.“It's all about education and talking to families about how bad these horrific diseases are, and I think we're winning the fight,” North Carolina pediatrician Dr. Christoph Diasio has told PCC. “Parents really do want to protect their children.”

While some parents oppose vaccines for religious reasons, others worry that the MMR vaccine causes autism. This assertion by British gastroenterologist Dr. Andrew Wakefield has since been discredited as fraudulent but continues to leave worried parents in its wake.

Measles is a highly contagious, acute viral illness that can lead to serious complications and death. The infection is spread by contact with droplets from the nose, mouth, or throat of an infected person. Sneezing and coughing disperses the droplets, which can linger in the air for several hours.

The measles vaccine first became available in 1963. The inoculations for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) were combined into one deliverable vaccine five years later, in 1971. Newborns should receive the first dose of MMR between ages 12 and 15 months. Children should receive a second, precautionary, dose of the vaccine between ages 4 and 6.

Those who have had the measles or who were vaccinated against the disease are immune.

Vermont pediatrician Dr. Joseph Hagan says herd immunity can be weakened as increasing numbers of people go unvaccinated. “This is a significant concern these days because the herd should have been immune,” he says.

Changing Perceptions

Dr. Hagan and his colleagues at Hagan, Rinehart & Connolly Pediatricians discuss with parents any concern they might have about vaccinations and share with them where to seek out medical information that is factual and scientifically-based. They also make it an imperative to try and change the mind of any parent who is swayed by the autism argument and wants to opt out of the vaccination process.

“Is it possible to change a parent's mind? Yes, I change people's minds all the time, but not necessarily the first time around,” Dr. Hagan says. “You can't be high pressure about it. You're dealing with people who are fearful and often untrusting, so you've got to build that trust.”

Dr. Diasio agrees: “We have fewer and fewer people who are worried, compared to a few years ago,” he said. “The science is pretty unshakeable, so are you going to believe anecdotes or believe science? We strongly encourage them to believe the science, and reassure them that vaccinating their child, like we do our own kids, is the best way to protect them."